Renal cell carcinoma

Signs and symptoms

The classic triad is hematuria (blood in the urine), flank pain and an abdominal mass. This triad only occurs in 10-15% of cases, and is generally indicative of more advanced disease. Today, the majority of renal tumors are asymptomatic and are detected incidentally on imaging, usually for an unrelated cause.

Signs may include:

- Abnormal urine color (dark, rusty, or brown) due to blood in the urine (found in 60% of cases)

- Loin pain (found in 40% of cases)

- Abdominal mass (25% of cases)

- Malaise, weight loss or anorexia (30% of cases)

- Polycythemia (5% of cases)

- Anaemia resulting from depression of erythropoietin (5% of cases)

- The presenting symptom may be due to metastatic disease, such as a pathologic fracture of the hip due to a metastasis to the bone

- Varicocele, the enlargement of one testicle, usually on the left (2% of cases). This is due to blockage of the left testicular vein by tumor invasion of the left renal vein; this typically does not occur on the right as the right gonadal vein drains directly into the inferior vena cava.

- Vision abnormalities

- Pallor or plethora

- Hirsutism – Excessive hair growth (females)

- Constipation

- Hypertension (high blood pressure) resulting from secretion of renin by the tumour (30% of cases)

- Elevated calcium levels (Hypercalcemia)

- Paraneoplastic disease

- Night Sweats

- Severe Weight Loss

Classification

Recent genetic studies have altered the approaches used in classifying renal cell carcinoma. The following system can be used to classify these tumors:

- Clear cell carcinoma (VHL and others on chromosome 3)

- Papillary carcinoma (MET, PRCC)

- Chromophobe renal carcinoma

- Collecting duct carcinoma

Renal epithelial neoplasms have characteristic cytogenetic aberrations that can aid in classification. See also Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology.

- Clear cell carcinoma: loss of 3p

- Papillary carcinoma: trisomy 7 and 17

- Chromophobe carcinoma: hypodiploid with loss of chromosomes 1, 2, 6, 10, 13, 17, 21

Array-based karyotyping can be used to identify characteristic chromosomal aberrations in renal tumors with challenging morphology. Array-based karyotyping performs well on paraffin embedded tumors and is amenable to routine clinical use. See also Virtual Karyotype for CLIA certified laboratories offering array-based karyotyping of solid tumors.

Other associated genes include TRC8, OGG1, HNF1A, HNF1B, TFE3, RCCP3, and RCC17.

Epidemiology

The incidence of renal cell cancer has been rising steadily. Nearly 51190 new diagnoses and 12890 deaths reported in the United States in 2007. It is more common in men than women: the male-to-female ratio is 1.6:1 and has been decreasing over the last decade. Blacks have a slightly higher rate of renal cell cancer than whites. The reasons for this are not clear. Note: in epidemiology, RCC is registered together with renal pelvis carcinoma, which is predominantly transitional cell type.

In Europe the incidence of RCC has doubled in the period from 1975 to 2005. RCC accounted for 3777 deaths in the UK in 2006; male 2372, female 1820.

Risk factors

Cigarette smoking and obesity are the strongest risk factors. Hypertension and a family history of the disease are also risk factors.

Dialysis patients with acquired cystic disease of the kidney showed a 30 times greater risk than in the general population for developing RCC.

Exposure to asbestos, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, gasoline has not been shown to be consistently associated with RCC risk.

Patients with certain inherited disorders such as von Hippel-Lindau disease, hereditary papillary renal cancer, a hereditary leiomyoma RCC syndrome and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, show an enhanced risk of RCC.

Diagnosis

By Signs and symptoms But unfortunately, early kidney cancers do not usually cause any signs or symptoms, but larger ones may.

Anamnesis (detailed medical review of past health state)

Physical examination A physical exam can provide information about signs of kidney cancer and other health problems. The doctor checks general signs of health and tests for fever and high blood pressure. and the doctor may be able to feel an abnormal mass when he or she examines your abdomen.

If a patient has symptoms that suggest kidney cancer, the doctor may perform one or more of the following procedures:

Lab tests Lab tests are not usually used to diagnose kidney cancer, but they can sometimes give the first hint that there may be a kidney problem. They are also done to get a sense of a person’s overall health and to help tell if cancer may have spread to other areas. They can help tell if a person is healthy enough to have an operation.

Urinalysis(Urine tests) These set of tests check for several indicators of the cancer such as blood, sugar, proteins, and bacteria.

Complete blood count A complete blood count can detect findings sometimes seen with renal cell cancer.

Blood chemistry tests Blood chemistry tests are usually done in people who may have kidney cancer, as it can affect the levels of certain chemicals in the blood.

Imaging tests Imaging tests use x-rays, magnetic fields, or radioactive substances to create pictures of the inside of your body. imaging tests can give doctors a reasonable amount of certainty that a kidney mass is (or is not) cancerous. Unlike most other cancers, doctors can often diagnose a kidney cancer fairly certainly without the need for a biopsy. In some patients, however, a biopsy may be needed to be sure.

Computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, intravenous pyelograms, and ultrasound can be very helpful in diagnosing most kinds of kidney tumors, although patients rarely need all of these tests.

Computed tomography(CT) This imaging test is similar with an x-ray test, and creates a detailed cross-sectional image of the body.Instead of taking one picture, like a regular x-ray, a CT scanner takes many pictures as it rotates around you while you lie on a table. And CT scan creates detailed images of the soft tissues in the body.

CT scanning is one of the most useful tests for finding and looking at a mass inside your kidney. It is also useful in checking whether or not a cancer has spread to organs and tissues beyond the kidney. The CT scan will provide precise information about the size, shape, and position of a tumor, and can help find enlarged lymph nodes that might contain cancer.

Magnetic resonance imaging(MRI) Like CT scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans provide detailed images of soft tissues in the body. But MRI scans use radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays. The energy from the radio waves is absorbed by the tissues and then revealed into a recognizable pattern on a special monitor.

They may be done in cases where CT scans aren’t practical, such as if a person is allergic to the CT contrast dye. MRI scans may also be done if there’s a chance that the cancer involves a major vein in the abdomen (the inferior vena cava), because they provide a better picture of blood vessels than CT scans.

But MRI scans are a little more uncomfortable than CT scans. First, they take longer — often up to an hour. Second, you have to lie inside a narrow tube, which is confining and can upset people with claustrophobia (a fear of enclosed spaces).

Ultrasound or ultrasonography Ultrasound imaging is a safe, noninvasive and brief test that can detect tumors. Ultrasound imaging is a medical technique that uses high-frequency sound waves to create an interior image of the body on a special computer screen. For this test, a small, microphone-like instrument called a transducer is placed on the skin near the kidney. Ultrasound can be helpful in determining if a kidney mass is solid or filled with fluid. The echo patterns produced by most kidney tumors look different from those of normal kidney tissue.

If a kidney biopsy is needed, this test can be used to guide a biopsy needle into the mass to obtain a sample.

Positron emission tomography(PET scan) This is a very specialized imaging technique that provides useful information about the tumor location and how far the cancer has spread. The Pet scan uses radioactive glucose (known as fluorodeoxyglucose or FDG) to locate the cancer, because the cancerous cells absorb a higher amount of this substance than normal tissues.

This test can be useful to see if the cancer may have spread to lymph nodes near the kidney. PET scans can also be useful if your doctor thinks the cancer may have spread but doesn’t know where.

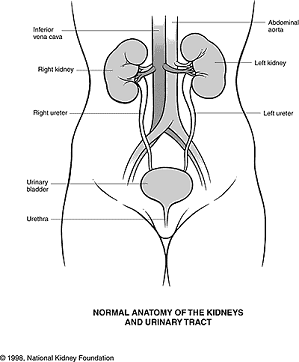

Intravenous pyelogram(IVP) The doctor injects dye into a vein in the arm. The dye travels from the bloodstream into the kidneys and then passes into the ureters and bladder. The dye makes them show up on x-rays. An IVP can be useful in finding abnormalities of the urinary tract, such as cancer, but you might not need an IVP if you have already had a CT or MRI.

Angiography Like the IVP, this type of x-ray also uses a contrast dye. the doctor administrates a contrast agent into an artery (usually renal artery) that carries the blood to the kidneys. This contrast agent is absorbed by the cancerous cells and displayed on an angiogram. Because angiography can outline the blood vessels that supply a kidney tumor, it can help a surgeon plan surgery in some patients who need blood vessels mapped before the operation. Angiography can also help diagnose renal cancers since the blood vessels usually have a special appearance with this test.

Other tests described here, such as chest x-rays and bone scans, are more often used to help determine if the cancer has spread (metastasized) to other parts of the body.

Chest x-ray

Bone scan

Biopsy Biopsies are not often used to diagnose kidney tumors. Imaging studies usually provide enough information. But, biopsy is sometimes used to get a small sample of cells from a suspicious area if imaging test results are not conclusive enough to warrant removing a kidney. Biopsy may also be done to confirm the diagnosis of cancer if a person’s health is too poor for surgery and other local treatments (such as radiofrequency ablation, arterial embolization or cryotherapy) are being considered. (10 questions to ask your doctor before a Biopsy)

Fine needle aspiration This procedure involves taking a sample of tissue from the tumor by using a thin needle attached to a syringe. Fine needle aspiration is performed only if the tumor can be easy reached. In kidney cancer patients, fine needle aspiration is the most used procedure of removing a sample of tissue.

Core needle biopsy This procedure is performed under local anesthesia and involves removing a small cylinder of tumor tissue.

Fuhrman grade The Fuhrman grade is determined by looking at kidney cancer cells (taken during a biopsy or during surgery) under a microscope. It is used by many doctors as a way to describe how aggressive the cancer is likely to be. The grade is based on how closely the cancer cells’ nuclei (part of a cell in which DNA is stored) look like those of normal kidney cells.

Renal cell cancers are usually graded on a scale of 1 through 4. Grade 1 renal cell cancers have cell nuclei that differ very little from normal kidney cell nuclei. These cancers usually grow and spread slowly and tend to have a good outlook (prognosis). At the other extreme, grade 4 renal cell cancer nuclei look quite different from normal kidney cell nuclei and have a worse prognosis.

Although the cell type and grade are sometimes helpful in predicting a prognosis, the cancer’s stage is by far the best predictor of survival. Staging is explained in Kidney cancer staging.

Pathology

Gross examination shows a yellowish, multilobulated tumor in the renal cortex, which frequently contains zones of necrosis, hemorrhage and scarring.

Light microscopy shows tumor cells forming cords, papillae, tubules or nests, and are atypical, polygonal and large. Because these cells accumulate glycogen and lipids, their cytoplasm appear “clear”, lipid-laden, the nuclei remain in the middle of the cells, and the cellular membrane is evident. Some cells may be smaller, with eosinophilic cytoplasm, resembling normal tubular cells. The stroma is reduced, but well vascularized. The tumor compresses the surrounding parenchyma, producing a pseudocapsule.

Secretion of vasoactive substances (e.g. renin) may cause arterial hypertension, and release of erythropoietin may cause erythrocytosis (increased production of red blood cells).

Radiology

The characteristic appearance of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a solid renal lesion which disturbs the renal contour. It will frequently have an irregular or lobulated margin. Traditonally 85 to 90%% of solid renal masses will turn out to be RCC but this number may be decreasing as renal masses are being found at smaller and smaller sizes with larger numbers of benign lesions. 10% of RCC will contain calcifications, and some contain macroscopic fat (likely due to invasion and encasement of the perirenal fat). Following intravenous contrast administration (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging), enhancement will be noted, and will highlight the tumor relative to normal renal parenchyma.

In particular, reliably distinguishing renal cell carcinoma from an oncocytoma (a benign lesion) is not possible using current medical imaging or percutaneous biopsy.

Renal cell carcinoma may also be cystic. As there are several benign cystic renal lesions (simple renal cyst, hemorrhagic renal cyst, multilocular cystic nephroma, polycystic kidney disease), it may occasionally be difficult for the radiologist to differentiate a benign cystic lesion from a malignant one. A classification system for cystic renal lesions that classifies them based specific imaging features into groups that are benign and those that need surgical resection is available.

At diagnosis, 30% of renal cell carcinoma has spread to that kidney’s renal vein, and 5-10% has continued on into the inferior vena cava.

Percutaneous biopsy can be performed by a radiologist using ultrasound or computed tomography to guide sampling of the tumor for the purpose of diagnosis. However this is not routinely performed because when the typical imaging features of renal cell carcinoma are present, the possibility of an incorrectly negative result together with the risk of a medical complication to the patient make it unfavorable from a risk-benefit perspective. This is not completely accurate, there are new experimental treatments.

Treatment

If it is only in the kidneys, which is about 40% of cases, it can be cured roughly 90% of the time with surgery. If it has spread outside of the kidneys, often into the lymph nodes or the main vein of the kidney, then it must be treated with adjunctive therapy, including cytoreductive surgery.rcc is resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy in most cases,but does respond well immunotherapy with interleukin 2 or interferon alpha,biologic,or targeted,therapy,and in early stage cases,cyrotherapy,and surgery.

Watchful waiting

Small renal tumors (< 4 cm) are treated increasingly by way of partial nephrectomy when possible. Most of these small renal masses manifest indolent biological behavior with excellent prognosis. More centers of excellence are incorporating needle biopsy to confirm the presence of malignant histology prior to recommending definitive surgical extirpation. In the elderly, patients with co-morbidities and in poor surgical candidates, small renal tumors may be monitored carefully with serial imaging. Most clinicians conservatively follow tumors up to a size threshold between 3–5 cm, beyond which the risk of distant spread (metastases) is about 5%.

Surgery

Micrograph of embolic material in a kidney removed because of renal cell carcinoma (cancer not shown). H&E stain.

Surgical removal of all or part of the kidney (nephrectomy) is recommended. This may include removal of the adrenal gland, retroperitoneal lymph nodes, and possibly tissues involved by direct extension (invasion) of the tumor into the surrounding tissues. In cases where the tumor has spread into the renal vein, inferior vena cava, and possibly the right atrium, this portion of the tumor can be surgically removed, as well. In cases of known metastases, surgical resection of the kidney (“cytoreductive nephrectomy”) may improve survival, as well as resection of a solitary metastatic lesion. Kidneys are sometimes embolized prior to surgery to minimize blood loss.

Surgery is increasingly performed via laparoscopic techniques. These have the advantage of being less of a burden for the patient and the disease-free survival is comparable to that of open surgery. For small exophytic lesions that do not extensively involve the major vessels or urinary collecting system, a partial nephrectomy (also referred to as “nephron sparing surgery”) can be performed. This may involve temporarily stopping blood flow to the kidney while the mass is removed as well as renal cooling with an ice slush. Mannitol can also be administered to help limit damage to the kidney. This is usually done through an open incision although smaller lesions can be done laparoscopically with or without robotic assistance.

Laparoscopic cryotherapy can also be done on smaller lesions. Typically a biopsy is taken at the time of treatment. Intraoperative ultrasound may be used to help guide placement of the freezing probes. Two freeze/thaw cycles are then performed to kill the tumor cells. As the tumor is not removed followup is more complicated (see below) and overall disease free rates are not as good as those obtained with surgical removal.

Percutaneous therapies

Percutaneous, image-guided therapies, usually managed by radiologists, are being offered to patients with localized tumor, but who are not good candidates for a surgical procedure. This sort of procedure involves placing a probe through the skin and into the tumor using real-time imaging of both the probe tip and the tumor by computed tomography, ultrasound, or even magnetic resonance imaging guidance, and then destroying the tumor with heat (radiofrequency ablation) or cold (cryotherapy). These modalities are at a disadvantage compared to traditional surgery in that pathologic confirmation of complete tumor destruction is not possible. Therefore, long-term follow-up is crucial to assess completeness of tumour ablation.

Medications

RCC “elicits an immune response, which occasionally results in dramatic spontaneous remissions.” This has encouraged a strategy of using immunomodulating therapies, such as cancer vaccines and interleukin-2 (IL-2), to reproduce this response. IL-2 has produced “durable remissions” in a small number of patients, but with substantial toxicity. Another strategy is to restore the function of the VHL gene, which is to destroy proteins that promote inappropriate vascularization. Bevacizumab, an antibody to VEGF, has significantly prolonged time to progression, but phase 3 trials have not been published. Sunitinib (Sutent), sorafenib (Nexavar), and temsirolimus, which are small-molecule inhibitors of proteins, have been approved by the U.S. F.D.A.

Sorafenib, a protein kinase inhibitor, was FDA approved in December 2005 for treatment of advanced renal cell cancer.

A month later, Sunitinib was approved as well. Sunitinib—an oral, small-molecule, multi-targeted (RTK) inhibitor—and sorafenib both interfere with tumor growth by inhibiting angiogenesis as well as tumor cell proliferation. Sunitinib appears to offer greater potency against advanced RCC, perhaps because it inhibits more receptors than sorafenib. However, these agents have not been directly compared against one another in a single trial.

Recently the first Phase III study comparing an RTKI with cytokine therapy was published in the New England Journal of Medicine. This study showed that Sunitinib offered superior efficacy compared with interferon-α. Progression-free survival (primary endpoint) was more than doubled. The benefit for sunitinib was significant across all major patient subgroups, including those with a poor prognosis at baseline. 28% of sunitinib patients had significant tumor shrinkage compared with only 5% of patients who received interferon-α. Although overall survival data are not yet mature, there is a clear trend toward improved survival with sunitinib. Patients receiving sunitinib also reported a significantly better quality of life than those treated with IFNa.

Temsirolimus (CCI-779) is an inhibitor of mTOR kinase (mammalian target of rapamycin) that was shown to prolong overall survival vs. interferon-α in patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma with three or more poor prognostic features. The results of this Phase III randomized study were presented at the 2006 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (www.ASCO.org).

Date of Approval: March 30, 2009 Company: Novartis AG Treatment for: Renal Cell Carcinoma Afinitor (everolimus) is an oral once-daily inhibitor of mTOR indicated for the treatment of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) after failure of treatment with sunitinib or sorafenib. Afinitor approved in US as first treatment for patients with advanced kidney cancer after failure of either sunitinib or sorafenib – March 30, 2009

Chemotherapy

Most of the currently available cytostatics are ineffective for the treatment of RCC. Their use can not be recommended for the treatment of patients with metastasized RCC,as response rates are very low,often just 5-15%,and most responses are short lived. The use of Tyrosine Kinase (TK) inhibitors, such as Sunitinib and Sorafenib, and Temsirolimus are described in a different section

Vaccine

Cancer vaccines, such as TroVax, have shown promising results in phase 2 trials for treatment of renal cell carcinoma. However, issues of tumor immunosuppression and lack of identified tumor-associated antigens must be addressed before vaccine therapy can be applied successfully in advanced renal cell cancer.

Prognosis

The five year survival rate is around 90-95% for tumors less than 4 cm. For larger tumors confined to the kidney without venous invasion, survival is still relatively good at 80-85%. For tumors that extend through the renal capsule and out of the local fascial investments, the survivability reduces to near 60%. If it has metastasized to the lymph nodes, the 5-year survival is around 5 % to 15 %. If it has spread metastatically to other organs, the 5-year survival rate is less than 5 %.

For those that have tumor recurrence after surgery, the prognosis is generally poor. Renal cell carcinoma does not generally respond to chemotherapy or radiation. Immunotherapy, which attempts to induce the body to attack the remaining cancer cells, has shown promise. Recent trials are testing newer agents, though the current complete remission rate with these approaches are still low, around 12-20% in most series.however,new tyrosine kinease inhibators including nexavar,pazopnib,and rapamycin have greatly improved prognosis for advanced RCC since 2004.