Prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is a form of cancer that develops in the prostate, a gland in the male reproductive system. The cancer cells may metastasize (spread) from the prostate to other parts of the body, particularly the bones and lymph nodes. Prostate cancer may cause pain, difficulty in urinating, problems during sexual intercourse, or erectile dysfunction. Other symptoms can potentially develop during later stages of the disease.

Rates of detection of prostate cancers vary widely across the world, with South and East Asia detecting less frequently than in Europe, and especially the United States.[1] Prostate cancer tends to develop in men over the age of fifty and although it is one of the most prevalent types of cancer in men, many never have symptoms, undergo no therapy, and eventually die of other causes. This is because cancer of the prostate is, in most cases, slow-growing, symptom free and men with the condition often die of causes unrelated to the prostate cancer, such as heart/circulatory disease, pneumonia, other unconnected cancers, or old age. Many factors, including genetics and diet, have been implicated in the development of prostate cancer. The presence of prostate cancer may be indicated by symptoms, physical examination, prostate specific antigen (PSA), or biopsy. There is controversy about the accuracy of the PSA test and the value of screening. Suspected prostate cancer is typically confirmed by taking a biopsy of the prostate and examining it under a microscope. Further tests, such as CT scans and bone scans, may be performed to determine whether prostate cancer has spread.

Treatment options for prostate cancer with intent to cure are primarily surgery, radiation therapy, and proton therapy. Other treatments, such as hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, cryosurgery, and high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) also exist, depending on the clinical scenario and desired outcome.

The age and underlying health of the man, the extent of metastasis, appearance under the microscope, and response of the cancer to initial treatment are important in determining the outcome of the disease. The decision whether or not to treat localized prostate cancer (a tumor that is contained within the prostate) with curative intent is a patient trade-off between the expected beneficial and harmful effects in terms of patient survival and quality of life.

Classification

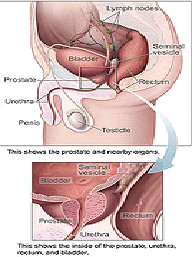

The prostate is a part of the male reproductive organ that helps make and store seminal fluid. In adult men, a typical prostate is about three centimeters long and weighs about twenty grams. It is located in the pelvis, under the urinary bladder and in front of the rectum. The prostate surrounds part of the urethra, the tube that carries urine from the bladder during urination and semen during ejaculation. Because of its location, prostate diseases often affect urination, ejaculation, and rarely defecation. The prostate contains many small glands which make about twenty percent of the fluid constituting semen.[4] In prostate cancer, the cells of these prostate glands mutate into cancer cells. The prostate glands require male hormones, known as androgens, to work properly. Androgens include testosterone, which is made in the testes; dehydroepiandrosterone, made in the adrenal glands; and dihydrotestosterone, which is converted from testosterone within the prostate itself. Androgens are also responsible for secondary sex characteristics such as facial hair and increased muscle mass.

An important part of evaluating prostate cancer is determining the stage, or how far the cancer has spread. Knowing the stage helps define prognosis and is useful when selecting therapies. The most common system is the four-stage TNM system (abbreviated from Tumor/Nodes/Metastases). Its components include the size of the tumor, the number of involved lymph nodes, and the presence of any other metastases.

The most important distinction made by any staging system is whether or not the cancer is still confined to the prostate. In the TNM system, clinical T1 and T2 cancers are found only in the prostate, while T3 and T4 cancers have spread elsewhere. Several tests can be used to look for evidence of spread. These include computed tomography to evaluate spread within the pelvis, bone scans to look for spread to the bones, and endorectal coil magnetic resonance imaging to closely evaluate the prostatic capsule and the seminal vesicles. Bone scans should reveal osteoblastic appearance due to increased bone density in the areas of bone metastasis—opposite to what is found in many other cancers that metastasize.

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) currently do not add any significant information in the assessment of possible lymph node metastases in patients with prostate cancer according to a meta-analysis. The sensitivity of CT was 42% and specificity of CT was 82%. The sensitivity of MRI was 39% and the specificity of MRI was 82%. For patients at similar risk to those in this study (17% had positive pelvic lymph nodes in the CT studies and 30% had positive pelvic lymph nodes in the MRI studies), this leads to a positive predictive value (PPV) of 32.3% with CT, 48.1% with MRI, and negative predictive value (NPV) of 87.3% with CT, 75.8% with MRI.

After a prostate biopsy, a pathologist looks at the samples under a microscope. If cancer is present, the pathologist reports the grade of the tumor. The grade tells how much the tumor tissue differs from normal prostate tissue and suggests how fast the tumor is likely to grow. The Gleason system is used to grade prostate tumors from 2 to 10, where a Gleason score of 10 indicates the most abnormalities. The pathologist assigns a number from 1 to 5 for the most common pattern observed under the microscope, then does the same for the second-most-common pattern. The sum of these two numbers is the Gleason score. The Whitmore-Jewett stage is another method sometimes used. Proper grading of the tumor is critical, since the grade of the tumor is one of the major factors used to determine the treatment recommendation.

Signs and symptoms

Early prostate cancer usually causes no symptoms. Often it is diagnosed during the workup for an elevated PSA noticed during a routine checkup. It’s highly advised to avoid sexual intercourse for 3 days prior to a PSA test because that does affect the outcome of the test. Sometimes, however, prostate cancer does cause symptoms, often similar to those of diseases such as benign prostatic hypertrophy. These include frequent urination, increased urination at night, difficulty starting and maintaining a steady stream of urine, blood in the urine, and painful urination. Prostate cancer is associated with urinary dysfunction as the prostate gland surrounds the prostatic urethra. Changes within the gland, therefore, directly affect urinary function. Because the vas deferens deposits seminal fluid into the prostatic urethra, and secretions from the prostate gland itself are included in semen content, prostate cancer may also cause problems with sexual function and performance, such as difficulty achieving erection or painful ejaculation.

Advanced prostate cancer can spread to other parts of the body, possibly causing additional symptoms. The most common symptom is bone pain, often in the vertebrae (bones of the spine), pelvis, or ribs. Spread of cancer into other bones such as the femur is usually to the proximal part of the bone. Prostate cancer in the spine can also compress the spinal cord, causing leg weakness and urinary and fecal incontinence.

Causes

The specific causes of prostate cancer remain unknown. A man’s risk of developing prostate cancer is related to his age (unusual under the age of 50), genetics, race, diet, lifestyle, medications, and other factors. The primary risk factor is age. Prostate cancer is uncommon in men younger than 45, but becomes more common with advancing age. The average age at the time of diagnosis is 70. However, many men never know they have prostate cancer. Autopsy studies of Chinese, German, Israeli, Jamaican, Swedish, and Ugandan men who died of other causes have found prostate cancer in thirty percent of men in their 50s, and in eighty percent of men in their 70s. In the year 2005 in the United States, there were an estimated 230,000 new cases of prostate cancer and 30,000 deaths due to prostate cancer. Men with high blood pressure are more likely to develop prostate cancer.

Genetics

Genetic background may contribute to prostate cancer risk, as suggested by associations with race, family, and specific gene variants. In the United States, prostate cancer more commonly affects black men than white or Hispanic men, and is also more deadly in black men. In contrast, the incidence and mortality rates for Hispanic men are one third lower than for non-Hispanic whites. Men who have a brother or father with prostate cancer have twice the risk of developing prostate cancer. Studies of twins in Scandinavia suggest that forty percent of prostate cancer risk can be explained by inherited factors.

No single gene is responsible for prostate cancer; many different genes have been implicated. Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, important risk factors for ovarian cancer and breast cancer in women, have also been implicated in prostate cancer. Other linked genes include the “prostate cancer gene”, HPC1, the androgen receptor, and the vitamin D receptor. The TEMPRSS2-ETS fusion gene exists in many prostate cancer cases and helps prostate cancer cells to survive and grow.

Diet

Dietary amounts of certain foods, vitamins, and minerals can contribute to prostate cancer risk. Dietary factors that may decrease prostate cancer risk include the mineral selenium. A study in 2007 cast doubt on the effectiveness of lycopene (found in tomatoes) in reducing the risk of prostate cancer. Lower blood levels of vitamin D also may increase the risk of developing prostate cancer. This may be linked to lower exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light, since UV light exposure can increase vitamin D in the body.

A large study has implicated dairy, specifically low-fat milk and other dairy products to which vitamin A palmitate has been added. This form of synthetic vitamin A has been linked to prostate cancer because it reacts with zinc and protein to form an unabsorbable complex. Research studies suggest a relationship between an increased intake of proteins, total fat, saturated fat, oleic acid, and vitamin A during ages of 30-49 and an increased risk of prostate cancer. The association is highly significant for vitamin A and approaches statistical significance for the other four nutrients. One explanation of vitamin A’s effect on risk of prostate cancer is based on the disturbance of the zinc-retinol binding protein-vitamin A axis.

Folic acid supplements have recently been linked to an increase in risk of developing prostate cancer. Recently a ten year research study led by University of Southern California researchers showed that men who took daily folic acid supplements of 1 mg were three times more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer than men who took a placebo. Folate plays a complex role in prostate cancer and folic acid supplements have a different effect on prostate cancer than folate naturally found in foods. The supplement form, folic acid, is more bioavailable in the body compared with dietary sources of folate. Folate hydrolase activity is associated with prostate-specific antigen and it is found that a large amount of both folate hydrolase activity and prostate-specific antigen in specifically prostate cancer. Unmetabolized folate is in relation with a decreased amount of natural killer T cell, which will make the immune system more vulnurable to malignant growth of cancer cells. However, it is important to note that dietary adequate intake of folate has an inverse effect with developing prostate cancer.

A Swedish study of 254 subjects, a median age of 64, and a follow up of 5 years showed that folate status is not protective against prostate cancer and may even result in a 3 fold increase in early prostate cancer development and risk. Supplements and multivitamins, alcohol and drug consumption, GI disorders, and folate bioavailability were not analyzed in this study.

High alcohol intake may increase the risk of prostate cancer and interfere with folate metabolism. Low folate intake and high alcohol intake may increase the risk of prostate cancer to a greater extent than the sole effect of either one by itself. A case control study consisting of 137 veterans addressed this hypothesis and the results were that high folate intake was related to a 79% lower risk of developing prostate cancer and there was no association between alcohol consumption by itself and prostate cancer risk. Folate’s effect however was only significant when coupled with low alcohol intake. There is a significant decrease in risk of prostate cancer with increasing dietary folate intake but this association only remains in individuals with low levels of alcohol consumption. There was no association found in this study between folic acid supplements and risk of prostate cancer.

The prostate gland has a high concentration of zinc so it has been hypothesized that zinc plays a role in prostate cancer. Recently researchers studied the relationship between zinc supplement intake of 100 mg/day and the risk of prostate cancer in 46 974 US men over a 14 year period and found that long term zinc supplement intake may play a role in prostate carcinogenesis.

Medication exposure

There are also some links between prostate cancer and medications, medical procedures, and medical conditions. Daily use of anti-inflammatory medicines such as aspirin, ibuprofen, or naproxen may decrease prostate cancer risk. Use of the cholesterol-lowering drugs known as the statins may also decrease prostate cancer risk. Infection or inflammation of the prostate (prostatitis) may increase the chance for prostate cancer. In particular, infection with the sexually transmitted infections chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis seems to increase risk. Finally, obesity and elevated blood levels of testosterone may increase the risk for prostate cancer. There is an association between vasectomy and prostate cancer however more research is needed to determine if this is a causative relationship.

Research released in May 2007, found that US war veterans who had been exposed to Agent Orange had a 48% increased risk of prostate cancer recurrence following surgery.

Potential viral cause

In 2006, researchers associated a previously unknown retrovirus, Xenotropic MuLV-related virus or XMRV, with human prostate tumors. Subsequent reports on the virus have been contradictory. A group of US researchers found XMRV protein expression in human prostate tumors, while German scientists failed to find XMRV-specific antibodies or XMRV-specific nucleic acid sequences in prostate cancer samples.

Pathophysiology

When normal cells are damaged beyond repair, they are eliminated by apoptosis. Cancer cells avoid apoptosis and continue to multiply in an unregulated manner.

Prostate cancer is classified as an adenocarcinoma, or glandular cancer, that begins when normal semen-secreting prostate gland cells mutate into cancer cells. The region of prostate gland where the adenocarcinoma is most common is the peripheral zone. Initially, small clumps of cancer cells remain confined to otherwise normal prostate glands, a condition known as carcinoma in situ or prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN). Although there is no proof that PIN is a cancer precursor, it is closely associated with cancer. Over time, these cancer cells begin to multiply and spread to the surrounding prostate tissue (the stroma) forming a tumor. Eventually, the tumor may grow large enough to invade nearby organs such as the seminal vesicles or the rectum, or the tumor cells may develop the ability to travel in the bloodstream and lymphatic system. Prostate cancer is considered a malignant tumor because it is a mass of cells that can invade other parts of the body. This invasion of other organs is called metastasis. Prostate cancer most commonly metastasizes to the bones, lymph nodes, rectum, and bladder. Runx2 is a transcription factor that prevents cancer cells from undergoing apoptosis thereby contributing to the development of prostate cancer. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated protein-1 (TRAP-1)is a mitochondrial protein that inhibits the apoptosis pathway and helps prostate cancer cells to survive and grow. The PI3k/Akt signaling cascade works with the transforming growth factor beta/SMAD signaling cascade to ensure prostate cancer cell survival and protection against apoptosis. X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) is hypothesized to promote prostate cancer cell survival and growth and is a target of research because if this inhibitor can be shut down then the apoptosis cascade can carry on its function in preventing cancer cell proliferation. Macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 (MIC-1) stimulates the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling pathway which leads to prostate cancer cell growth and survival. The androgen receptor helps prostate cancer cells to survive and is a target for many anti cancer research studies; so far, inhibiting the androgen receptor has only proven to be effective in mouse studies. Prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) stimulates the development of prostate cancer by increasing folate levels for the cancer cells to use to survive and grow; PSMA increases available folates for use by hydrolyzing glutamated folates.

Diagnosis

The only test that can fully confirm the diagnosis of prostate cancer is a biopsy, the removal of small pieces of the prostate for microscopic examination. However, prior to a biopsy, several other tools may be used to gather more information about the prostate and the urinary tract. Digital rectal examination may allow a doctor to detect prostate abnormalities. Cystoscopy shows the urinary tract from inside the bladder, using a thin, flexible camera tube inserted down the urethra. Transrectal ultrasonography creates a picture of the prostate using sound waves from a probe in the rectum.

Biopsy

If cancer is suspected, a biopsy is offered. During a biopsy a urologist or radiologist obtains tissue samples from the prostate via the rectum. A biopsy gun inserts and removes special hollow-core needles (usually three to six on each side of the prostate) in less than a second. Prostate biopsies are routinely done on an outpatient basis and rarely require hospitalization. Fifty-five percent of men report discomfort during prostate biopsy.

Gleason score

The tissue samples are then examined under a microscope to determine whether cancer cells are present, and to evaluate the microscopic features (or Gleason score) of any cancer found. Prostate specific membrane antigen is a transmembrane carboxypeptidase and exhibits folate hydrolase activity. This protein is overexpressed in prostate cancer tissues and is associated with a higher Gleason score.

Tumor markers

Tissue samples can be stained for the presence of PSA and other tumor markers in order to determine the origin of maligant cells that have metastasized. Small cell carcinoma is a type of prostate cancer that cannot be diagnosed using the PSA. Currently researchers are trying to determine the best way to screen for this type of prostate cancer because it is a relatively unknown and rare type of prostate cancer but very serious and quick to spread to other parts of the body.

Possible methods include chromatographic separation methods by mass spectrometry, or protein capturing by immunoassays or immunized antibodies. The test method will involve quantifying the amount of the biomarker PCI, with reference to the Gleason Score. Not only is this test quick, it is also sensitive. It can detect patients in the diagnostic grey zone, particularly those with a serum free to total Prostate Specific Antigen ratio of 10-20%.

Diagnostic tools under investigation

At present, an active area of research involves non-invasive methods of prostate tumor detection. Adenoviruses modified to transfect tumor cells with harmless yet distinct genes (such as luciferase) have proven capable of early detection. So far, however, this area of research has been tested only in animal and LNCaP models.

PCA3

Another potential non-invasive method of early prostate tumor detection is through a molecular test that detects the presence of cell-associated PCA3 mRNA in urine. PCA3 mRNA is expressed almost exclusively by prostate cells and has been shown to be highly over-expressed in prostate cancer cells. PCA3 is not a replacement for PSA but an additional tool to help decide whether, in men suspected of having prostate cancer, a biopsy is really needed. The higher the expression of PCA3 in urine, the greater the likelihood of a positive biopsy, i.e., the presence of cancer cells in the prostate.

Early prostate cancer

It was reported in April 2007 that a new blood test for early prostate cancer antigen-2 (EPCA-2) that may alert men if they have prostate cancer and how aggressive it will be is being researched.[53][54] Thrombophlebitis is associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer and may be a good way for physicians to remind themselves to screen patients with thrombophlebitis for prostate cancer as well since these two are closely linked.

Prostate mapping

Prostate mapping is a method of diagnosis that may be accurate in determining the precise location and aggressiveness of a tumor. It uses a combination of multi-sequence MRI imaging techniques and a template-guided biopsy system, and involves taking multiple biopsies through the skin that lies in front of the rectum rather than through the rectum itself. The procedure is carried out under general anesthetic.

Prostasomes

Epithelial cells of the prostate secrete prostasomes as well as PSA. Prostasomes are membrane–surrounded, prostate-derived organelles that appear extracellularly, and one of their physiological functions is to protect the sperm from attacks by the female immune system. Cancerous prostate cells continue to synthesize and secrete prostasomes, and may be shielded against immunological attacks by these prostasomes. Research of several aspects of prostasomal involvement in prostate cancer has been performed.

Prevention

Food, vitamins and medication

Evidence from epidemiological studies supports a possible protective role in reducing prostate cancer for dietary Vitamin B6, selenium, vitamin E, lycopene, and soy foods. High plasma levels of Vitamin D may also have a protective effect. Estrogens from fermented soybeans and other plant sources (called phytoestrogens) may also help prevent prostate cancer. The selective estrogen receptor modulator drug toremifene has shown promise in early trials. Two medications which block the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, finasteride and dutasteride, have also shown some promise. The use of these medications for primary prevention is still in the testing phase, and they are not widely used for this purpose. The initial problem with these medications is that they may preferentially block the development of lower-grade prostate tumors, leading to a relatively greater chance of higher grade cancers, and negating any overall survival improvement. More recent research found that finasteride did not increase the percentage of higher grade cancers. A 2008 study update found that finasteride reduces the incidence of prostate cancer by 30%. In the original study it turns that that the smaller prostate caused by finasteride means that a doctor is more likely to hit upon cancer nests and more likely to find aggressive-looking cells. Most of the men in the study who had cancer — aggressive or not — chose to be treated and many had their prostates removed. A pathologist then carefully examined every one of those 500 prostates and compared the kinds of cancers found at surgery to those initially diagnosed at biopsy. Finasteride did not increase the risk of High-Grade prostate cancer.

Green tea may be protective (due to its polyphenol content), although the most comprehensive clinical study indicates that it has no protective effect. A 2006 study of green tea derivatives demonstrated promising prostate cancer prevention in patients at high risk for the disease. Recent research published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute suggests that taking multivitamins more than seven times a week can increase the risks of contracting the disease. This research was unable to highlight the exact vitamins responsible for this increase (almost double), although they suggest that vitamin A, vitamin E and beta-carotene may lie at its heart. It is advised that those taking multivitamins never exceed the stated daily dose on the label. Scientists recommend a healthy, well balanced diet rich in fiber, and to reduce intake of meat. A 2007 study published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute found that men eating cauliflower, broccoli, or one of the other cruciferous vegetables, more than once a week were 40% less likely to develop prostate cancer than men who rarely ate those vegetables. The phytochemicals indole-3-carbinol and diindolylmethane, found in cruciferous vegetables, has antiandrogenic and immune modulating properties.

A comprehensive worldwide report Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective compiled by the World Cancer Research Fund and the American Institute for Cancer Research reports a significant relation between lifestyle (including food consumption) and cancer prevention. A healthy lifestyle plays a crucial role in the prevention of prostate cancer. Exercise and diet may help prevent prostate cancer to the same extent as medications such as alpha-blockers and 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors. Many doctors prescribe supplements to prostate cancer patients but currently the efficacy of nutrient supplements is still unknown. Supplements may not be as beneficial to prostate health as micronutrients obatined naturally from the diet.

Beta carotene may protect against prostate cancer in nonsmoking men. Vitamin E may decrease the risk of prostate cancer in smokers but has no effect in nonsmokers. Selenium is an antioxidant mineral and may reduce the risk of prostate cancer by 26%. The prostate gland has the highest zinc concentration of any soft tissue, which decreases significantly during prostate cancer. Zinc may help to prevent or slow cancer by inhibiting terminal oxidation, inducing apoptosis, maintaining DNA integrity, and inhibiting tumor growth.

Ejaculation frequency

More frequent ejaculation also may decrease a man’s risk of prostate cancer. One study showed that men who ejaculated five times a week in their 20s had a decreased rate of prostate cancer, though other studies have shown no benefit. The results contradict those of previous studies, which have suggested that having had many sexual partners, or a high frequency of sexual activity, increases the risk of prostate cancer by up to 40 percent. The key difference is that these earlier studies defined sexual activity as sexual intercourse, whereas this study focused on the number of ejaculations, whether or not intercourse was involved. Another study completed in 2004 reported that “Most categories of ejaculation frequency were unrelated to risk of prostate cancer. However, high ejaculation frequency was related to decreased risk of total prostate cancer.” The report abstract concluded, “Our results suggest that ejaculation frequency is not related to increased risk of prostate cancer.” A 2008 study showed that men who engaged in frequent masturbation, of about two to seven times a week, at the ages of 20s and 30s, had a higher rate of prostate cancer, while men who engaged in frequent masturbation, once a week, at the age of 50s had a lower rate.

Oils and fatty acids

In experimental models using mice have been tested, dietary and serum omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) increased prostate tumor growth,and has sped up histopathological progression, and decreased survival, while the omega-3 fatty acids, in the same situation, had the opposite, beneficial effect.

Men with high serum linoleic acid, but not palmitic, can reduce the risk of prostate cancer by taking tocopherol supplementation.

Men with elevated levels of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA) had lowered incidence.

A long-term study reports that “blood levels of trans fatty acids, in particular trans fats resulting from the hydrogenation of vegetable oils, are associated with an increased prostate cancer risk.”

Some researchers have indicated that serum myristic acid and palmitic acid and dietary myristic and palmitic saturated fatty acids and serum palmitic combined with alpha-tocopherol supplementation are associated with increased risk of prostate cancer in a dose-dependent manner. Serum association of these and other saturated fatty acids was also investigated by another study.

The American Dietetic Association and Dieticians of Canada report a decreased incidence of prostate cancer for those following a vegetarian diet.

Other

The membrane androgen receptor prevents prostate cancer cells from growing and surviving by stimulating the apoptosis cascade.

Screening

Prostate cancer screening is an attempt to find unsuspected cancers. Screening tests may lead to more specific follow-up tests such as a biopsy, where small cores of the prostate are removed for closer study. Prostate cancer screening options include the digital rectal exam and the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test. Screening for prostate cancer is controversial because it is expensive and it is not at all clear whether the benefits of screening outweigh the risks of follow-up diagnostic tests and cancer treatments and the unnecessary worry for the patient that often ensues.

Prostate cancer is usually a slow-growing cancer, very common among older men. In fact, most prostate cancers never grow to the point where they cause symptoms, and most men with prostate cancer die of other causes before prostate cancer has an impact on their lives. The PSA screening test may detect these small cancers that would never become life-threatening. Doing the PSA test in these men may lead to overdiagnosis, including additional testing and treatment. Follow-up tests, such as prostate biopsy, may cause pain, bleeding and infection. Prostate cancer treatments may cause urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction. A large randomized study in which 76,000 men were randomized to receive either PSA screening or conventional care found that more men that underwent PSA screening were diagnosed with prostate cancer, but that there was no difference in mortality between the two groups.

Management

Treatment for prostate cancer may involve active surveillance, surgery (i.e. radical prostatectomy), radiation therapy including brachytherapy (prostate brachytherapy) and external beam radiation therapy, High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), chemotherapy, oral chemotherapeutic drugs (Temozolomide/TMZ), positron emission tomography, cryosurgery, hormonal therapy, or some combination. Which option is best depends on the stage of the disease, the Gleason score, and the PSA level. Other important factors are the man’s age, his general health, and his feelings about potential treatments and their possible side-effects. Because all treatments can have significant side-effects, such as erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence, treatment discussions often focus on balancing the goals of therapy with the risks of lifestyle alterations. Prostate cancer patients are strongly recommended to work closely with their urologist and use a combination of the treatment options when managing their prostate cancer.

The selection of treatment options may be a complex decision involving many factors. For example, radical prostatectomy after primary radiation failure is a very technically challenging surgery and may not be an option. This may enter into the treatment decision.

If the cancer has spread beyond the prostate, treatment options significantly change, so most doctors that treat prostate cancer use a variety of nomograms to predict the probability of spread. Treatment by watchful waiting/active surveillance, HIFU, external beam radiation therapy, brachytherapy, cryosurgery, and surgery are, in general, offered to men whose cancer remains within the prostate. Hormonal therapy and chemotherapy are often reserved for disease that has spread beyond the prostate. However, there are exceptions: radiation therapy may be used for some advanced tumors, and hormonal therapy is used for some early stage tumors. Cryotherapy (the process of freezing the tumor), hormonal therapy, and chemotherapy may also be offered if initial treatment fails and the cancer progresses.

Prostate cancer can be treated by using Ad.DD3-E1A-IL-24 which stimulates apoptosis in cancer cells thereby inhibiting tumor growth.

Prognosis

Prostate cancer rates are higher and prognosis poorer in developed countries than the rest of the world. Many of the risk factors for prostate cancer are more prevalent in the developed world, including longer life expectancy and diets high in red meat and reduced-fat dairy products to which vitamin A palmitate has been added. (People that consume larger amounts of meat and dairy also tend to consume fewer portions of fruits and vegetables. It is not currently clear whether both of these factors, or just one of them, contribute to the occurrence of prostate cancer.) Also, where there is more access to screening programs, there is a higher detection rate. Prostate cancer is the ninth-most-common cancer in the world, but is the number-one non-skin cancer in United States men. Prostate cancer affected eighteen percent of American men and caused death in three percent in 2005. In Japan, death from prostate cancer was one-fifth to one-half the rates in the United States and Europe in the 1990s. In India in the 1990s, half of the people with prostate cancer confined to the prostate died within ten years. African-American men have 50–60 times more prostate cancer and prostate cancer deaths than men in Shanghai, China. In Nigeria, two percent of men develop prostate cancer and 64% of them are dead after two years.

In patients that undergo treatment, the most important clinical prognostic indicators of disease outcome are stage, pre-therapy PSA level and Gleason score. In general, the higher the grade and the stage the poorer the prognosis. Nomograms can be used to calculate the estimated risk of the individual patient. The predictions are based on the experience of large groups of patients suffering from cancers at various stages.

In 1941, Charles Huggins reported that androgen ablation therapy causes regression of primary and metastatic androgen-dependent prostate cancer. Androgen ablation therapy causes remission in 80-90% of patients undergoing therapy, resulting in a median progression-free survival of 12 to 33 months. After remission, an androgen-independent phenotype typically emerges, wherein the median overall survival is 23–37 months from the time of initiation of androgen ablation therapy. The actual mechanism contributes to the progression of prostate cancer is not clear and may vary between individual patient. A few possible mechanisms have been proposed. Androgen at a concentration of 10-fold higher than the physiological concentration has also been shown to cause growth suppression and reversion of androgen-independent prostate cancer xenografts or androgen-independent prostate tumors derived in vivo model to an androgen-stimulated phenotype in athymic mice. These observation suggest the possibility to use androgen to treat the development of relapsed androgen-independent prostate tumors in patients. Oral infusion of green tea polyphenols, a potential alternative therapy for prostate cancer by natural compounds, has been shown to inhibit the development, progression, and metastasis as well in autochthonous transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP) model, which spontaneously develops prostate cancer.